The Dark Man

Irish and Celtic myths and legends, Irish folklore and Irish fairy tales from the Fenian Cycle

Fionn faces his greatest challenge, The Dark Man

Now it is known by some that the fairies of Ireland weren't much like the fairies we hear about in these latter days, harmless things of mischief and frolic, but were instead respected and often feared, for their anger was quick and their kindness was whimsical. Some would join men in battle, and some would make war on men, others were omens of ill fortune and it was a brave, even foolish fellow who'd build his house on a fairy fort!

But of all the fairies in all the lands of this world or the world of the Sidhe, none were more feared than an Fear Dorcha, or the Dark Man, he who lurks, he who stalks, the one from Outside, the Dark Druid of the Sidhe.

But of all the fairies in all the lands of this world or the world of the Sidhe, none were more feared than an Fear Dorcha, or the Dark Man, he who lurks, he who stalks, the one from Outside, the Dark Druid of the Sidhe.

Not as much is told as might be known about this fairy, for even to whisper his name was to invite his attention, and by repute he was none too fond of people sharing his ways and habits, even to knocking on the moonlit doors of those who made glib gossip of him.

Tall he was and narrow of frame, clad always in black or dark material, with a face you'd never quite see for your eyes would slide away like a stumbling child on a frozen lake, and you'd be glad of it for such waters could swallow you whole!

As the years of the Sidhe pass differently to our own, he's most often dressed in fashions a little out of date, but cut well and dapper for all that. He serves as the fairy Queen's Taker, as it was known, when she needed a mortal he'd be the one sent to gather them, whether child or elder made no odds to him. On his black horse he rode the highways and lanes of Ireland, going about his business with neither fear nor favour, and those he came for in the night were never heard from again.

Three brothers he had, Fear Dearg, the red man of the red coat and the cruel jest, Fear Gorta, the hungry man whose coming presages famine and woe, and an Fear Liath Mór, the great grey man who brings fogs to wreck ships and terrorises those who climb in high mountains, causing them to fall to their deaths from the heights.

Across the many worlds and in secret places he's known, travelling with the Queen's court to do her bidding, and there is no charm or means to turn him aside, even to the great Fionn Mac Cumhaill!

For this is the tale of the wife of Fionn.

There was a young lady of the Sidhe that the Dark Man had taken a fancy to whose name was Sadhbh, but she spurned his love, so in vengeance he used his sorcery to turn her into a fawn. For three long years she ate little but grass and drank only such waters as could be found flowing freely, until one of the Dark Man's servants took pity on her and told her that the power of the fell fae would have no sway in the house of her true love, a man by the name of Fionn MacCumhaill. She ran straight to Fionn's place of strength to wait nearby, and sure enough before too long Fionn came out with hounds for hunting.

Well neither of his dogs Bran and Sceolan would touch the fawn, but instead leaped and played about the creature, licking its face, and rubbing delighted noses against its neck.

Fionn came up then. His long spear was lowered in his fist at the thrust, and his sharp knife was in its sheath, but he did not use them, for the fawn and the two hounds began to play round him, and the fawn was as affectionate towards him as the hounds were, so that when a velvet nose was thrust in his palm, it was as often a fawn's muzzle as a hound's.

When the others reached home, Fionn told of his hunt, and it was agreed that such a fawn must not be killed, but that it should be kept and well treated, and that it should be the pet fawn of the Fianna.

Late that night, when he was preparing for rest, the door of Fionn's chamber opened gently and a young woman came into the room. He stared at her, as he well might, for he had never seen or imagined to see a woman so beautiful as this was. Indeed, she was not a woman, but a young girl, and her bearing was so gently noble, her look so modestly high, that the champion dared scarcely look at her, although he could not by any means have looked away.

“She is the sky-woman of the dawn,” he said. “She is the light on the foam. She is white and odorous as an apple-blossom. She smells of spice and honey. She is my beloved beyond the women of the world. She shall never be taken from me.”

So they spoke and she asked of him his protection, and so smitten was he that he could hardly say other than that her enemy was his own. He asked her the name of this fearsome foe, and the terror that was in her heart was on her face.

“He is everywhere,” she whispered. “He is in the bushes, and on the hill. He looked up at me from the water, and he stared down on me from the sky. His voice commands out of the spaces, and it demands secretly in the heart. He is not here or there, he is in all places at all times. I cannot escape from him,” she said, “and I am afraid,” and at that she wept noiselessly and looked on Fionn.

And as she gazed she felt in her own heart the deep love that had sprung upon Fionn, so the two fell into one another's arms and were married from that day. So deep was his love for her that he didn't join the hunt again, or feast with the men of the Fianna nor listen to the sweet words of poets or the wisdom of magicians, for in his wife he found all that and more. And not one foot did his wife step outside his house all the time they were together.

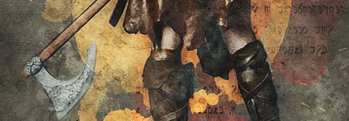

It came to pass some years later that a great fleet of the Danes came around the cliffs of Ben Edair, bent on war and slave-taking, so Fionn was called by his stern duty to see them off. He had little love for the northmen to begin with and to be called away from his wife was further insult to the injury they dealt, so he made his way with haste and saw them off with brutal vigour.

After the battle he wanted to get back home as quickly as he could, so he left before the feasting and celebrations could take place, much to the dismay of his men.

“In love he is,” Conan grumbled. “A cordial for women, a disease for men, a state of wretchedness.”

“Wretched in truth,” Fionn murmured. “Love makes us poor. We have not eyes enough to see all that is to be seen, nor hands enough to seize the tenth of all we want. When I look in her eyes I am tormented because I am not looking at her lips, and when I see her lips my soul cries out, 'Look at her eyes, look at her eyes.'”

“That is how it happens,” said Goll rememberingly.

“That way and no other,” Caelte agreed.

And the champions sighed in memory of their own loves, and knew Fionn would go.

But when he came to his house he found the servants running about in a state of distress, shouting and pointing aimlessly, and there was a general effort on the part of each to get behind the other.

Calling the chief of the servants, a man called Gariv Cronan, to him, Fionn demanded to know what was amiss.

"When you had been away for a day the guards were surprised. They were looking from the heights of the Dun, and the Flower of Allen was with them. She, for she had a queen's eye, called out that the master of the Fianna was coming over the ridges to the Dun, and she ran from the keep to meet you.”

“It was not I,” said Fionn.

“It bore your shape,” replied Gariv Cronan. “It had your armour and your face, and the dogs, Bran and Sceolan, were with it.”

“We were distrustful," the servant continued. "We had never known Fionn to return from a combat before it had been fought, and we knew you could not have reached Ben Edair or encountered the Norsemen. So we urged our lady to let us go out to meet you, but to remain herself in the Dun.”

“She cried on us, 'Let me go to meet my husband, the father of the child that is not born!'”

At these words Fionn put his hand before his eyes, seeing all that happened.

“Tell on your tale,” said he.

“She ran to those arms, and when she reached them the figure lifted its hand. It touched her with a hazel rod, and, while we looked, she disappeared, and where she had been there was a fawn standing and shivering. The fawn turned and bounded towards the gate of the Dun, but the hounds that were near chased after her.”

Fionn stared at him like a lost man.

“And they dragged her back to the figure that seemed to be Fionn. Three times she broke away and came bounding to us, and three times the dogs took her by the throat and dragged her back.”

“You stood to look!” snarled Fionn, suddenly wrathful.

“No, master, we ran, but she vanished as we got to her; the great hounds vanished away, and that being that seemed to be Fionn became a tall and dark man whose face was hidden, and disappeared with them. We were left in the rough grass, staring about us and at each other, listening to the moan of the wind and the terror of our hearts.”

Fionn stood as though he were dumb and blind, and now and again he beat terribly on his breast with his closed fist, as though he would kill that within him which should be dead and could not die. He went so, beating on his breast, to his inner room in the Dun, and he was not seen again for the rest of that day, nor until the sun rose over the plain in the morning.

For many years after Fionn sought high and low for his wife, scouring the glens and mountains, turning over every stone that might hide a way to the land of the Sidhe, taking counsel with the wise who would not speak for fear of the Dark Man, and each night he slept alone and in great misery, awaking to sorrow the next day.

When he hunted he brought only the hounds that he trusted, Bran and Sceolan, Lomaire, Brod, and Lomlu, for if a fawn was chased each of these five great dogs would know if that was a fawn to be killed or one to be protected, and so there was little risk to his wife and a small hope of finding her.

After seven years he was out so hunting when from a narrow place high on Benbulbin there came a great howling and snarling of dogs. Racing to the spot Fionn beheld his five wise hounds in a circle giving ferocious battle to a hundred black dogs!

They were bristling and terrible, and each bite from those great, keen jaws was woe to the beast that received it. Nor did they fight in silence as was their custom and training, but between each onslaught the great heads were uplifted, and they pealed loudly, mournfully, urgently, for their master.

With a mighty roar Fionn and his men joined the fray, and when they'd seen off the dogs they found a little boy in the circle his hounds had protected, not a bit afraid, and Fionn lifted him up. The boy looked down on him, and in the noble trust and fearlessness of that regard Fionn's heart melted away.

“My little fawn!” he said.

“My little fawn!” he said.

And he remembered that other fawn. He set the boy between his knees and stared at him earnestly and long.

“There is surely the same look,” he said to his wakening heart, “that is the very eye of my wife.”

The grief flooded out of him at a stroke, and joy foamed into it in one great tide. He marched back singing to the encampment, and men saw once more the merry Fionn they had almost forgotten.

When the boy grew older he told Fionn what he could recall, which in truth wasn't much, but that he had grown in a wide, beautiful place. There were hills and valleys there, and woods and streams, but in whatever direction he went he came always to a cliff, so tall it seemed to lean against the sky, and so straight that even a goat would not have imagined to climb it.

He had no companion there but only a deer who would lead him to food and play with him. None other did he see save only a dark stern man who used to speak with the deer. Sometimes he talked gently and softly and coaxingly, but at times again he would shout loudly and in a harsh, angry voice. But whatever way he talked the deer would draw away from him in dread, and he always left her at last furiously.

“The last time I saw the deer,” the child continued, “the dark man was speaking to her. He spoke for a long time. He spoke gently and angrily, and gently and angrily, so that I thought he would never stop talking, but in the end he struck her with a hazel rod, so that she was forced to follow him when he went away. She was looking back at me all the time and she was crying so bitterly that any one would pity her. I tried to follow her also, but I could not move, and I cried after her too, with rage and grief, until I could see her no more and hear her no more. Then I fell on the grass, my senses went away from me, and when I awoke I was on the hill in the middle of the hounds where you found me.”

That boy's name was then Oisín, chief of all the poets in the world, and a mighty warrior too, but his is a story for another day. Marked below is the house of Fionn on the Hill of Allen.

More Legends from the Fenian Cycle

The days of the heroes of the Fianna have captured the imaginations of many throughout the ages, and one such was the ninth century poet Gofraidh Fionn O’Dalaigh, one of the finest poets in all of Killarney and all of Ireland. For it was his pen and none other that first put quill and ink to parchment and recorded the old story of Reicne F ... [more]

It was a fine day in Ireland many years ago when Fionn and his Fianna took a fancy to go out hunting. Warm was the sun amid the whispering glades of ancient forests, gentle was the breeze and sweet the scent of summer flowers in its bosom. Sweeter yet was the sight of a mighty deer to the eyes of the hunters, and so they gave chase, howling with de ... [more]

It was in the days of Fionn and the Fianna, a very long time ago in Ireland, that the people of Ben Edair decided to hold a festival, a Feis or Aonach, to celebrate the season. All of Fionn’s hosts were gathered, the seven ordinary warbands and the seven extraordinary warbands, and they danced and played music merrily with the people. Then ... [more]

There are few these days who have not heard of Fionn Mac Cumhaill, hero and defender of Ireland, or at least might recognise his name. But there were no creatures that Fionn loved amongst his three hundred dogs more than his two favourites, Bran and Sceolan, meaning Raven and Survivor, and though it’s a stranger story than most, this is the t ... [more]

It is not unusual for stories in the Irish legendarium to have more than one meaning besides that of a literal recounting of historical events, whether by accident or by design. Some tales were meant to be understood in the context of the era and culture of the story teller, while others might instruct in certain arts, and yet others contain myster ... [more]

Those monks who recorded the mythologies and folklore of Ireland which had previously been passed down by word of mouth from bard to druid to bard for countless generations were, by their very nature, devout Christians. As Christians they were dedicated to not only God and His Church, but to the people who bore and nurtured them, and everywhere the ... [more]

One day Fionn Mac Cumhaill, doughty hero of Ireland, and his friends Goll, Cialta and Oscar, as well as others of the Fianna, were resting after the hunt on a certain long hill now known by a different name. Their meal was being made ready, when what should happen only a girl of the kin of the giants came striding up and sat down among them, a grea ... [more]

Something which often appears in the most ancient tales of Ireland is the grisly vision of heads which speak after being separated from their bodies! This was said to be an art of the druids inherited from the necromancy of the Dé Danann, who were themselves said to be able to raise a whole army from the grave to fight again day after day! ... [more]

There once was a young fellow called Conall, and he lived with his parents in the east of the country. They lived a quiet life, catching fish and digging up oysters for meat and lamps, but one dark day the Fomors came and demanded tribute. Having none to give, his father bid the sea demons begone, but instead they made to take himself and his famil ... [more]

Young Fionn Mac Cumhaill was out walking with his dog Bran one fine morning, and he happened to pass into a deep and thick dark wood of the kind that once covered all of Ireland, for the hunting was better there, when what did he come across but a thousand horses hauling timber and men chopping down the trees and preparing the logs. "What a ... [more]

There was a mighty warrior in the west of Eriu, and Cumhal Mac Art was his name. Feared was his axe and he could skewer two men with a single cast of his feathered war-dart, and yet for all that he lived a lonely life, and a life of fear – for it had been foretold that should he ever marry, he would die in battle the very next day! But all ... [more]

It was in the day of Fionn Mac Cumhaill when he was an old man, yet still hale and hearty, that one of his warriors, whose name was Diarmaid son of Donn and grandson of Duibne, had carried off his young bride-to-be, Gráinne daughter of Cormac! The two had fallen in love and Gráinne, for all of Fionn's fame, wanted nothing to do wi ... [more]

One warm summer's day Fionn and his men were out hunting through the darkling forests of Ballachgowan in Munster, chasing deer and boar through the gloomy glades, when they stopped short all of a sudden and came face to face with a startling sight! For what had stepped between them and their prey but a strange, damp giant of a man. Black wer ... [more]

Fionn Mac Cumhaill stood at the door of his hunting lodge with his fists on his hips, his heart sinking as he realised his intentions to hunt for deer this day were lost in the waves of mist and fog that had rolled in from Dublin bay, although at that time it was known by a different name. It had come as far inland as Gleann na Smol, the Glen of th ... [more]

When Fionn Mac Cumhaill became leader of the Fianna, the fiercest and most warlike of those bands of heroes who lived in the wild places, hunting and acting as champions for their kings, and defending Ireland from evil, he decided that he wished to have only the best warriors to follow him. So he sat down and sucked his thumb to taste the wisdom ... [more]

Close by where Limerick city stands today lie the ruins of an ancient and once mighty fortress called Carrigogunnel, which commanded all the lands about with a stern hand. It was known then as a place of ill omen, and it is known today as the same, for it was once the home of an uncanny hag by the name of Gráinne. Amid the surrounding mar ... [more]

A dark horde of fell-handed warriors approached Ireland, sails gathered off the coast like storm clouds, billowing out in the gusts of uncertain wind, while oars bent to the rolling thunder of drums. Fierce indeed was the host of King Colgan, master of Lochlainn, and he came to make war on Cormac Mac Airt, High King of Ireland! As soon as Fionn ... [more]

Diarmuid the Fair, son of Donn or Duibhne of the Tuatha De Danann was one of the Fianna, the great warriors of ancient Ireland who protected the land from dangers near and far. It was said that no woman could resist his gaze, for he'd been granted the blessing of comeliness by the Ghost Queen Morrigan after he helped her out of a spot of bother ... [more]

Fionn Mac Cumhaill and the rest of the Fianna were resting after a great battle, weary and sore with sorrow at the loss of their fellows, when they spied coming along the shores of Loch Lein in County Kerry a beautiful young woman riding a swift horse, so swift indeed that its hooves scarcely seemed to touch the ground! Now although the women of ... [more]

Now it is known by some that the fairies of Ireland weren't much like the fairies we hear about in these latter days, harmless things of mischief and frolic, but were instead respected and often feared, for their anger was quick and their kindness was whimsical. Some would join men in battle, and some would make war on men, others were omens of ... [more]

It was a fine brisk spring morning in Ireland when Fionn Mac Cumhaill decided to take himself for a stroll along the white sandy beaches of the seashore, the better to breathe the air and enjoy the simple pleasures life had to offer. But that morning, life had more to offer and it didn't look pleasant, for it was a giant bearing down on the bea ... [more]

Fionn MacCumhaill was well known as a fair and handsome man, but his most distinguishing feature was his grey hair - and he was not born with it! Fionn was one time out on the green of Almhuin, and he saw what had the appearance of a grey fawn running across the plain. He called and whistled to his hounds then, but neither hound nor man heard hi ... [more]

After his seven years of training with the poet Finegas were done, Fionn Mac Cumhaill took himself from the river Boyne to the great hall of the High King in Tara, Conn of the Hundred Battles, to present himself there as a member of the Fianna, the very best of the best warriors throughout Ireland. Announcing himself, Conn took him into the band an ... [more]

Here is the story of how Fionn MacCumhaill gained the knowledge of the world. And wouldn't it be a great thing to know it all? Still, knowledge and wisdom must be balanced, and this was known to the young man called Fionn, which means fair and bright. He was fleeing from the warriors who had murdered his father when he came upon the hiding plac ... [more]