Serpent Cults in Ancient Ireland

Irish and Celtic myths and legends, Irish folklore and Irish fairy tales from the Fenian Cycle

The slither of scales in the darkness

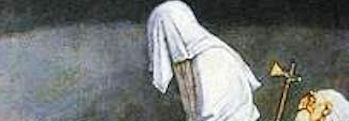

Those monks who recorded the mythologies and folklore of Ireland which had previously been passed down by word of mouth from bard to druid to bard for countless generations were, by their very nature, devout Christians. As Christians they were dedicated to not only God and His Church, but to the people who bore and nurtured them, and everywhere they endeavoured to preserve the ancient stories of their homelands. And for this we owe them a great debt of gratitude.

Those monks who recorded the mythologies and folklore of Ireland which had previously been passed down by word of mouth from bard to druid to bard for countless generations were, by their very nature, devout Christians. As Christians they were dedicated to not only God and His Church, but to the people who bore and nurtured them, and everywhere they endeavoured to preserve the ancient stories of their homelands. And for this we owe them a great debt of gratitude.

Naturally enough, being Christian, they felt and had no obligation to preserve superstitious pagan beliefs, and they removed most mentions of such beliefs whenever they found them, or may have confused ancestor-reverence with a different kind of religion.

Yet we may still glimpse some of the strange beliefs held by the pre-Christian people of Ireland, who freely and willingly gave up those practices for the light of the Christian faith.

Saint Patrick’s most famous feat was in driving all of the snakes out of Ireland – but few believe he actually drove limbless reptiles into the ocean! Mind you, so rare and unheard-of were snakes in Ireland that during medieval times it was believed that wood from an Irish tree was able to repel serpents, and any attempt to bring a snake into the country would cause its death. Even being near an Irish stone was believed to kill snakes.

An old tradition at the time held that Niul, the husband of Pharaoh's daughter Scota, had a son, Gael, who was bitten by a serpent in the wilderness. Brought before Moses, he was not only healed, but was told that no serpent should have power wherever he or his descendants should dwell.

As this hero subsequently moved to Eireann, that would explain the absence of the venomous plague from the Isle of Saints. Yet even writers like Solinus who came to Ireland centuries before Saint Patrick noticed the absence of serpents.

So what did the great Saint cleanse from Ireland? None other than the snake cults of old.

Throughout almost all ancient pagan lands there were certain common spiritual threads, such as the mother of monsters, the worship of ancestors, and the adoration of the serpent idol. Everywhere we look in the ancient world these can be found, and still they can be found in modern day China and India, in the form of dragon-gods and Rivaan, king of the serpents.

In South America these creatures were represented by an entity called "Pachamama", often depicted as a huge dragon that caused earthquakes when displeased, and demanding human sacrifices.

Other accounts of these serpent cults can be found in early Christian writing, as in St Justin Martyr's First Apology, chapter 27 - Guilt of exposing children, where he details the hair-raising practices of these groups:

"and they refer these mysteries to the mother of the gods, and along with each of those whom you esteem gods there is painted a serpent, a great symbol and mystery"

When armies marched to war in ancient Ireland they would carry the banner of the serpent before them. Some believe that early Irish spiral and curling motifs found in place like Newgrange represented the serpent, or as they were known at the time, the péists or god-worms who lived in lakes and deep holes or wells.

These creatures were worshipped by cultists and magicians in secret, for they demanded fell sacrifices and strange rituals, and plagued the land wherever they arose. Whispered rumours followed after their wending trails, that they were of the mighty Nephilim who had somehow survived the cleansing flood. Dark knowledge did they grant to their followers, the better to trouble mankind.

Long before Saint Patrick came to Ireland, Fionn Mac Cumahaill had songs sung of his hunts for these mighty menaces

“It resembled a great mound —

Its jaws were yawning wide

There might lie concealed, though great its fury,

A hundred champions in its eye-pits.

Taller in height than eight men,

Was its tail, which was erect above its back

Thicker was the most slender part of its tail,

Than the forest oak which was sunk by the flood.”

And in Lough Cuan

“We found a serpent in that lake.

His being there was no gain to us

On looking at it as we approached,

Its head was larger than a hill.

Larger than any tree in the forest.

Were its tusks of the ugliest shape

Wider than the portals of a city

Were the ears of the serpent as we approached.”

More were scourged before his blade in Lough Cuilinn and Lough Neagh, in Lough Rea, as well as the blue serpent of Eirne, and one at Howth. He killed two at Glen Inny, one in the murmuring Bann, another at Lough Carra, and beheaded a fearful creature which cast fire at him from Lough Leary.

“A serpent there was in the Lough of the mountain,

Which caused the slaughter of the Fianna

Twenty hundred or more

It put to death in one day.”

Important to this cult was the serpent-stone, a flinty circle which was used to cure illness or cast spells. One such was used by the druid Mogh Ruith in his battle against King Cormac, when he cast it into the river after praising it most worshipfully and it turned into a fiery snake, strangling his enemies.

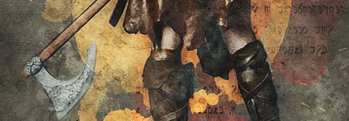

Briefly were the red altars returned when the Vikings came to Ireland aboard their dragon-ships, marked with the sign of the serpent upon their prow and telling tales of Jörmungandr the world serpent, ouroboros, who would destroy the earth if he ever awoke, but good king Brian Borúmna saw them off after long years of depredations.

And yet there are rumours that vestiges of the old serpent cults persisted late in rustic parts of Ireland! A man called Windele, of Kilkenny, wrote:

“Even as late as the eleventh century, we have evidence of the prevalence of the old religion in the remoter districts, and in many of the islands on our western coasts. Many of the secondary doctrines of Druidism hold their ground at this very day as articles of faith.

Connected with these practices (belteine, &c.), is the vivid memory still retained of once universal Ophiolatreia, or serpent worship, and the attributing of supernatural powers and virtues to particular animals, such as the bull, the white and red cow, the boar, the horse, the dog, &c., the memory of which has been perpetuated in our topographical denominations.”

Perhaps the reason there are no snakes in Ireland is because natural serpents can sense the nearness of their less canny kin. So be careful should you stray into the unpeopled parts of old Ireland and find there a deep and watery hole, for who knows what may lurk yet in its gloomstruck depths!

Loughrea, where one of these dread monsters of the old world was slain, is marked on the map below!

More Legends from the Fenian Cycle

The days of the heroes of the Fianna have captured the imaginations of many throughout the ages, and one such was the ninth century poet Gofraidh Fionn O’Dalaigh, one of the finest poets in all of Killarney and all of Ireland. For it was his pen and none other that first put quill and ink to parchment and recorded the old story of Reicne F ... [more]

It was a fine day in Ireland many years ago when Fionn and his Fianna took a fancy to go out hunting. Warm was the sun amid the whispering glades of ancient forests, gentle was the breeze and sweet the scent of summer flowers in its bosom. Sweeter yet was the sight of a mighty deer to the eyes of the hunters, and so they gave chase, howling with de ... [more]

It was in the days of Fionn and the Fianna, a very long time ago in Ireland, that the people of Ben Edair decided to hold a festival, a Feis or Aonach, to celebrate the season. All of Fionn’s hosts were gathered, the seven ordinary warbands and the seven extraordinary warbands, and they danced and played music merrily with the people. Then ... [more]

There are few these days who have not heard of Fionn Mac Cumhaill, hero and defender of Ireland, or at least might recognise his name. But there were no creatures that Fionn loved amongst his three hundred dogs more than his two favourites, Bran and Sceolan, meaning Raven and Survivor, and though it’s a stranger story than most, this is the t ... [more]

It is not unusual for stories in the Irish legendarium to have more than one meaning besides that of a literal recounting of historical events, whether by accident or by design. Some tales were meant to be understood in the context of the era and culture of the story teller, while others might instruct in certain arts, and yet others contain myster ... [more]

Those monks who recorded the mythologies and folklore of Ireland which had previously been passed down by word of mouth from bard to druid to bard for countless generations were, by their very nature, devout Christians. As Christians they were dedicated to not only God and His Church, but to the people who bore and nurtured them, and everywhere the ... [more]

One day Fionn Mac Cumhaill, doughty hero of Ireland, and his friends Goll, Cialta and Oscar, as well as others of the Fianna, were resting after the hunt on a certain long hill now known by a different name. Their meal was being made ready, when what should happen only a girl of the kin of the giants came striding up and sat down among them, a grea ... [more]

Something which often appears in the most ancient tales of Ireland is the grisly vision of heads which speak after being separated from their bodies! This was said to be an art of the druids inherited from the necromancy of the Dé Danann, who were themselves said to be able to raise a whole army from the grave to fight again day after day! ... [more]

There once was a young fellow called Conall, and he lived with his parents in the east of the country. They lived a quiet life, catching fish and digging up oysters for meat and lamps, but one dark day the Fomors came and demanded tribute. Having none to give, his father bid the sea demons begone, but instead they made to take himself and his famil ... [more]

Young Fionn Mac Cumhaill was out walking with his dog Bran one fine morning, and he happened to pass into a deep and thick dark wood of the kind that once covered all of Ireland, for the hunting was better there, when what did he come across but a thousand horses hauling timber and men chopping down the trees and preparing the logs. "What a ... [more]

There was a mighty warrior in the west of Eriu, and Cumhal Mac Art was his name. Feared was his axe and he could skewer two men with a single cast of his feathered war-dart, and yet for all that he lived a lonely life, and a life of fear – for it had been foretold that should he ever marry, he would die in battle the very next day! But all ... [more]

It was in the day of Fionn Mac Cumhaill when he was an old man, yet still hale and hearty, that one of his warriors, whose name was Diarmaid son of Donn and grandson of Duibne, had carried off his young bride-to-be, Gráinne daughter of Cormac! The two had fallen in love and Gráinne, for all of Fionn's fame, wanted nothing to do wi ... [more]

One warm summer's day Fionn and his men were out hunting through the darkling forests of Ballachgowan in Munster, chasing deer and boar through the gloomy glades, when they stopped short all of a sudden and came face to face with a startling sight! For what had stepped between them and their prey but a strange, damp giant of a man. Black wer ... [more]

Fionn Mac Cumhaill stood at the door of his hunting lodge with his fists on his hips, his heart sinking as he realised his intentions to hunt for deer this day were lost in the waves of mist and fog that had rolled in from Dublin bay, although at that time it was known by a different name. It had come as far inland as Gleann na Smol, the Glen of th ... [more]

When Fionn Mac Cumhaill became leader of the Fianna, the fiercest and most warlike of those bands of heroes who lived in the wild places, hunting and acting as champions for their kings, and defending Ireland from evil, he decided that he wished to have only the best warriors to follow him. So he sat down and sucked his thumb to taste the wisdom ... [more]

Close by where Limerick city stands today lie the ruins of an ancient and once mighty fortress called Carrigogunnel, which commanded all the lands about with a stern hand. It was known then as a place of ill omen, and it is known today as the same, for it was once the home of an uncanny hag by the name of Gráinne. Amid the surrounding mar ... [more]

A dark horde of fell-handed warriors approached Ireland, sails gathered off the coast like storm clouds, billowing out in the gusts of uncertain wind, while oars bent to the rolling thunder of drums. Fierce indeed was the host of King Colgan, master of Lochlainn, and he came to make war on Cormac Mac Airt, High King of Ireland! As soon as Fionn ... [more]

Diarmuid the Fair, son of Donn or Duibhne of the Tuatha De Danann was one of the Fianna, the great warriors of ancient Ireland who protected the land from dangers near and far. It was said that no woman could resist his gaze, for he'd been granted the blessing of comeliness by the Ghost Queen Morrigan after he helped her out of a spot of bother ... [more]

Fionn Mac Cumhaill and the rest of the Fianna were resting after a great battle, weary and sore with sorrow at the loss of their fellows, when they spied coming along the shores of Loch Lein in County Kerry a beautiful young woman riding a swift horse, so swift indeed that its hooves scarcely seemed to touch the ground! Now although the women of ... [more]

Now it is known by some that the fairies of Ireland weren't much like the fairies we hear about in these latter days, harmless things of mischief and frolic, but were instead respected and often feared, for their anger was quick and their kindness was whimsical. Some would join men in battle, and some would make war on men, others were omens of ... [more]

It was a fine brisk spring morning in Ireland when Fionn Mac Cumhaill decided to take himself for a stroll along the white sandy beaches of the seashore, the better to breathe the air and enjoy the simple pleasures life had to offer. But that morning, life had more to offer and it didn't look pleasant, for it was a giant bearing down on the bea ... [more]

Fionn MacCumhaill was well known as a fair and handsome man, but his most distinguishing feature was his grey hair - and he was not born with it! Fionn was one time out on the green of Almhuin, and he saw what had the appearance of a grey fawn running across the plain. He called and whistled to his hounds then, but neither hound nor man heard hi ... [more]

After his seven years of training with the poet Finegas were done, Fionn Mac Cumhaill took himself from the river Boyne to the great hall of the High King in Tara, Conn of the Hundred Battles, to present himself there as a member of the Fianna, the very best of the best warriors throughout Ireland. Announcing himself, Conn took him into the band an ... [more]

Here is the story of how Fionn MacCumhaill gained the knowledge of the world. And wouldn't it be a great thing to know it all? Still, knowledge and wisdom must be balanced, and this was known to the young man called Fionn, which means fair and bright. He was fleeing from the warriors who had murdered his father when he came upon the hiding plac ... [more]