Fionn Mac Cumhaill Reborn

Irish and Celtic myths and legends, Irish folklore and Irish fairy tales from the Historical Cycle

The old magic of Ireland meets the new

Mongán mac Fíachnai was a prince of the Gaels, none other than he whose father was Fíachnae mac Báetáin, and it was about the seventh century in Ireland when he ruled over Ulster. Many are the tales told of him and his royal reign, with some even whispering that he was the son of Manannán mac Lir, ancient Gaelic Lord of the seas and oceans, even if such rumours were scorned by the new Christians in Ireland.

Mongán mac Fíachnai was a prince of the Gaels, none other than he whose father was Fíachnae mac Báetáin, and it was about the seventh century in Ireland when he ruled over Ulster. Many are the tales told of him and his royal reign, with some even whispering that he was the son of Manannán mac Lir, ancient Gaelic Lord of the seas and oceans, even if such rumours were scorned by the new Christians in Ireland.

Well, King Mongán of the Ulaid was in his circular stone hall in Rathmore of Moylinny when a poet came to him by the name of Forgoll. At that time in Ireland, poets were more than just storytellers and verse-singers, they were thought to have mystical powers and were held in the highest regard by all, and even kings walked in fear of a poet's wrath!

On this poet Mongán kept a wary eye however, since many a married couple had made complaint against him that he was abusing his status to take advantage of the women!

With that said, Forgoll was a masterful bard and tale-recounter, and every night he would recite a story to the king. So great was his lore that they heard a new story every night from Halloween to May day.

In gratitude and as was the custom, Mongán showered him with gifts and kept him well and comfortably.

But one day Mongán asked his poet about the death of Fothad Airgdech, a great Gaelic hero who died in battle with Fionn Mac Cumhaill, to which the poet replied that he'd been slain at Duffry in Leinster.

Whatever fit took hold of Mongán then, before he could consider his words, he frowned and denied the truth of what Forgoll said, which was nigh to the worst insult he could have thrown at any poet!

Infuriated, Forgoll, pale of face and shaking of hand, spat and swore he would satirise the king and despoil his memory and heritage for all generations to come. He would satirise not only the king but the memory of his father and his mother and his grandfather so that none would speak of them unless it was with mockery until the ending of the world!

Not content with that, he would sing his most baleful magics upon the waters of Ulster, so that fish should not be caught in their river-mouths. He would sing dark lays upon their woods, so that they should not give fruit, upon their plains, so that they should be barren forever of any produce.

Aghast, Mongán tried to calm him down with promises of precious jewels and gold to the value of seven cumals, which was the name for female slaves, or twice seven cumals, or three times seven!

Nothing would satisfy the poet, who stood still with a look of thunder on him.

Then the king he offered him one third of his land - no, one half of his land, or even his whole land, to no avail!

At last, humbled beyond measure, Mongán offered the poet anything except only his own liberty and that of his wife Breóthigernd, unless he could be shown to be right before the end of three days. The poet sneered at everything offered, but a strange gleam entered his eye when the king spoke of his wife. And so for the sake of his honour Mongán consented that Forgoll should iie with his wife.

Great was the sorrow of Breóthigernd, I can tell you! Tears unceasing flowed down her fair cheek, but Mongán told her not to be sorrowful, moved by the same strange spirit that had him contradict the poet in the first place, since help would certainly come to them.

So it came to the third day. The poet called at dawn, banging on the hall doors to enforce the agreement, but Mongán told him to wait till evening. He and his wife were in their bedroom and the woman wept as her surrender drew near and she saw no help. Mongán said only "Be not sorrowful, woman. He who is even now coming to our help, I hear his feet in the Labrinne."

Yet still she wept, and the king again said, "Weep not, my love! He who is now coming to our help, I hear his feet in the Máin." Thus they were waiting between every two watches of the day. She would weep, he would still say, "Weep not woman! He who is now coming to our help, I hear his feet in the Laune, in Lough Leane, in the Morning-star River between the Úi Fidgente and the Arada, in the Suir on Moy-Fevin in Munster, in the Echuir, in the Barrow, in the Liffey, in the Boyne, in the Dee, in the Newry river, in the Larne Water in front of Rathmore."

But at last when the sun fell and night came to them, Mongán was on his couch in his palace, and his wife at his right hand, and she sorrowful, dried of tears but broken of heart. The poet stood outside and called up in a loud, cheerful voice, summoning them to fulfil the bond agreed, but he was answered by the watch of the wall, who announced that a man approached the rath from the south.

His cloak was in a fold around him, and in his hand a headless spear-shaft that was both long and thick. Plunging the foot of the shaft into the earth outside the walls, the leaped across three ramparts, landed in the middle of the fortress, and then sauntered into the middle of the palace to face Mongán! Strange and difficult to gaze upon was his face, and the sight of him sent a chill through all present.

The king and the poet explained the cause of the queens grief - "I and the poet yonder," said Mongán, "have made a wager about the death of Fothad Airgdech. He said it was at Duffry in Leinster. I said that was false." Smiling darkly, the warrior said the poet was wrong.

"Then you are not among those who live," said the poet in a high and quavering voice, reaching now late in the day for his Christian cross, "only one who walked with Fionn Mac Cumhaill could contradict me!"

"Who could imagine such a thing!" said the warrior, but then he pointed at Mongán, "In truth we were with you, with Fionn, on that day!"

At these words a great murmuring arose among those present, for not only did the warrior seem to be of a most uncanny sort, he claimed their King was Fionn Mac Cumhaill reborn, after the old pagan ways!

Surprised and not a little worried, Mongán hushed him, looking around nervously for fear anyone might think he was lending credence to this blasphemy.

"Well," the nameless warrior smiled again, "we were with Fionn, then, and leave it at that. We came from Ailbe and met with Fothad Airgdech here on the Larne river where we fought a battle. I made a cast at him, throwing this very spear so that it passed through him and went into the earth beyond him and left its iron head in the earth."

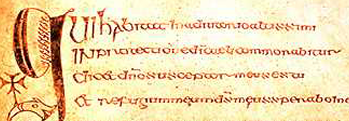

"This in my hand is the shaft that was in that spear. The bare stone from which I made that cast will be found, and the iron head will be found in the earth, and the tomb of Fothad Airgdech will be found a little to the east of it. A stone chest is about him there in the earth and upon the chest, are his two bracelets of silver, and his two arm-rings, and his neck-torc of silver. And by his tomb there is a stone pillar. And on the end of the pillar that is in the earth there is Ogam."

"This is what it says: This is Eochaid Airgdech. Cáilte slew him in an encounter against Fionn," and so they all knew the lost warrior's name.

They went with the warrior on the spot, and everything was found just as he claimed. It was Cáilte, Fionn's foster-son, that had come to them, and although he would never let it be said, Mongán was whispered to be Fionn Mac Cumhaill reborn.

Rathmore of Moylinny is marked on the map below!

More Tales from the Historical Cycle

A beautiful new font has been developed which allows you to type in Ogham on your computer! Dustin A. Ashley in association with Dr. Adam Dahmer are pushing the boundaries of Gaelic culture outwards into new and exciting territory, read on to learn more: "Within Gaelic culture, there is a long-standing tradition where lang ... [more]

High King Conn of the Hundred Battles, which in the way of the old people of Ireland meant battles without end rather than an exact measure and count of every affray he had been in, had overthrown all of the lesser kings of Ireland, the lords of the five Kingdoms and the lesser realms, and he had taken his seat in Tara. Not easy did he sit eithe ... [more]

Conn Cétchathach, or Conn of the Hundred Battles, was as his name suggested a mighty warrior-king of ancient Ireland. Some say it was after him that the province of Connacht was named, and he was made king after he accidentally stepped on the Lia Fáil, the coronation stone at Tara. It had been cast aside, lost, half buried and used as ... [more]

Mongán mac Fíachnai was a prince of the Gaels, none other than he whose father was Fíachnae mac Báetáin, and it was about the seventh century in Ireland when he ruled over Ulster. Many are the tales told of him and his royal reign, with some even whispering that he was the son of Manannán mac Lir, ancient G ... [more]

Díarmata mac Cerbaill was the last pagan High King of Ireland, who made his seat at Temair and followed the ancient rituals of inauguration, including the ban-feis or marriage to goddess of the land. His reign was a strange one where the mysteries of ancient Ireland vied with the light of Christianity and many powers rose and fell, often by ... [more]

Many centuries ago, on a windswept and hostile rock in the North Sea, a place called Iona, the great monk, philosopher and evangelist Colmcille founded a monastery. Men devoted to the new faith worked with fervour, bending their backs to hew from the pitiless stone, amid bleak and harsh weather, a place for worship and meditation upon the saviour o ... [more]

The extraordinary Ballintubber Abbey, known as Tobar Padraic in the Annals of the Four Mastersm is almost a thousand years old, having been built by King Cathal Crobdearg Ua Conchobair - whose father commissioned the beautiful Cross of Cong - in 1216. It has survived ages and centuries of persecution and fire, providing a place for people to visit ... [more]

One of the most imposing legacies of the last of the mighty megalith-builders of the Neolithic and Bronze ages, the Dolmen of the Four Maols, considered by some to be a cist tomb rather than a dolmen or portal tomb. An enormous capstone sits above three other stones, while the entry stone lies not far off. It was once covered by a cairn of smaller ... [more]

The gift of the gab, as it’s known, is a common thing among the Irish – being able to talk all day about anything and everything, and do it in a way that would have you listen as well. It’s as Irish as red hair and freckles. But what if you didn’t have the gift of the gab, or felt a deficiency of gabbiness? Never fear, al ... [more]

We are delighted to be able to present to you the rules of Fidchell, the Irish game of kings! This game can be purchased, but it's easy to get started and try it out for yourself. All you need is a 7 x 7 board, which can be squares or pins marked out - even on paper - 16 white or attacker pieces, a king piece, and 8 darker-coloured defender pie ... [more]

Ireland is full of strange little corners and odd byways that only a few know about, and one such is a mysterious place called the Gearagh, or An Gaorthadh, meaning the wooded river bed, in County Cork. Once it was part of the first forests in Ireland, home to verdant giants that grew after the great ice melted away, but now all that remains is a s ... [more]

Ireland at the beginning of the first millenium was a turbulent place, with many clans and kingdoms fighting among themselves, so that a Lord might be sitting comfortably one day but find himself fleeing for his life the next! And so it was with one of the greatest of Ireland's kings, Cormac Mac Art. Although he was by blood, law and custom ... [more]

On Martinmas eve, that is to say the 10th of November, it used to be the custom in many parts of Ireland to sacrifice an animal to Saint Martin of Tours! This tradition has only recently ceased, having been carried on well into living memory, as lately as the 1940s in some places. In poorer homes a goose, gander, duck or chicken was killed, whil ... [more]

It's true to say that music has a magic all to itself, for it can transport us to different places and times with the strumming of a few notes. It can make us feel angry, or sad, or happy, or any one of a myriad of other emotions. But if you were to hear the music of an occult Sidhe instrument played by one of the fairy folk under a loon's ... [more]

King Cormac Mac Airt was one of the mightiest kings of Ireland, known and well known for his wisdom, but after he lost an eye in a battle with the Déisi, he had to step down, for the solemn law was that a king must be without blemish. His son Cairbre came to him to ask his advice before in turn being crowned king. “O Cormac, grandso ... [more]

"Crom Cruach and his sub-gods twelve," Said Cormac "are but carven treene; The axe that made them, haft or helve, Had worthier of our worship been. "But He who made the tree to grow, And hid in earth the iron-stone, And made the man with mind to know The axe's use, is God alone." Anon to priests of Crom was ... [more]

Most people with an interest in Irish mythology and legends will have heard of the great tale of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, which tells of the heroic deeds of Cú Chulainn as he resisted and gave battle single handed to the armies of Queen Medb. What most don't know is that the ancient tale was once all but lost, for th ... [more]

One of the most legended and powerful relics of ancient Ireland was the Cathach, or battle-book of St Colmcille, who was also known as St Columba. A Cathach was really any sort of sacred or magical artifact, and great was the strife between the tribes and clans of Ireland to gain ownership of them! The psalter or prayer book of Saint Colmcille w ... [more]

Three was a sacred number to the people of ancient Ireland, bearing with it a hint of magic and the sacred, and this belief carried through to their spiritual practices, which occasionally included human sacrifice! Most cultures throughout history have at one point or another practised some form of human sacrifice, and lurid tales passed down fr ... [more]

Saint Colman was a famous Saint in early Irish Christianity, being born a prince not long after Saint Patrick brought the faith to Ireland in the first place. Despite his royal lineage however, his birth was no easy matter, for the druids had prophecised darkly that he would be a great man and surpass all others of his clan! His pregnant mother ... [more]

The old pagan times in Ireland were fraught with peril for even the mightiest warriors, with chieftains and tribes going to war often and for many reasons – pride, hatred, love and greed! And so it was with the fierce King Conall Collomrach. Little is known of his exploits, but his reign was brief and his end was violent, leaving behind only ... [more]

This now is the true tale of mighty King Cathal Mac Finguine of Munster, lord of Cork and warrior without peer. In ancient Ireland this story was told when mead was first brought out, or a prince sat to his feast, or when an inheritance was taken, and the reward for reciting this story was a white-spotted, red-eared cow, a shirt of new linen, or a ... [more]

The river in Meath which we today know as the Delvin, that very same river which flows into the Irish sea in Gormanstown, was not always called so. In the time of Kings it was called Inbher Oillbine, and this is the grim story of how it got that name. There was a prince who lived near to the mouth of the river, and his name was Ruadh Mac Righdui ... [more]

The boy who was to be Saint Colman was born in the northern kingdom of Dalriada, which held both Northern Ireland and Scotland in its power at the start of the sixth century. This was the time of the dawn of Christianity in Ireland, and it was a time when great terrors and monsters from primordial epochs still swam in the deep lakes and lazy rivers ... [more]

Most people have heard of Ireland's famous title, “The Island of Saints and Scholars”, and the reason it was so well known was because of the many fine Irish Catholic universities and colleges that preserved and spread learning throughout Europe. Of them all, there were few finer than the one in Howth, and so wonderful was its reput ... [more]

Very often here in Ireland we walk past the most astonishing buildings, carven stone high crosses, ancient temples and many similar things, but rarely do we wonder who built them. Well as it turns out, legend has it that a surprising number of them were built by a man called Gobán Saor, whose name means “Gobán the Builder,&rdquo ... [more]

I. Once upon a time there was a High King in Ireland by the name of Conn the hundred-fighter, for so many battles had he fought and won to gain his kingship. At the end of his reign was Fionn Mac Cumhaill born. Long was Conn's lineage, although I won't trouble you with the details, but he reigned at Tara of the Kings as Lord of all Irela ... [more]

In the time of High King Lugaid Luaigne, that is around the age when Fionn Mac Cumhaill and his Fianna fought in defence of the great land of Ireland, a dispute arose in the northern Kingdom among the men of the Ulaid, for instead of there being only one king of Ulster, there were two! Well, as anyone who knows anything about kings will tell you ... [more]

St Colmcille is one of the three patron saints of Ireland, and his life is the subject of story and legend. It was by his efforts that Christianity spread not only through Ireland but also Scotland, England and parts of Europe too! He was a tall and powerfully built man with a rich and melodious voice which, it was said, could be heard from one hil ... [more]

From the earliest times and in every corner of the world, mead was held in reverence. This sweet tasting fermented honey drink was especially loved by the ancient Irish, who shared fireside stories about rivers of mead in mystical lands over the edge of the ocean's horizon, ruled by Mannanan Mac Lír, and even in the place where the dead ... [more]

Ancient are the hills and mountains of Ireland, and ancient are her trees, something that the old people who lived here knew well. To them a tree was a mystical thing with its roots reaching down into the underworld of the sidhe mounds, and its branches lifting up high into the heavens towards the sun, moon and stars. Well over ten thousand places ... [more]

The Irish bee has been a beloved part of the culture and folklore as long as there have been people in Ireland, producing honey for cakes and mead as well as beeswax which has no end of uses. Many's the warm summer evening has been filled with their gentle humming above the beautiful flowers they help to pollinate. And yet for all that, old ... [more]

As Saint Patrick travelled across Ireland, spreading Christianity and the light among the pagan tribes, he saw many wonders and defeated many evils, but always more rose up to challenge him. So he took himself to prayer and saw a vision that he should travel to Croagh Patrick – although it was not so known at that time – and spend the L ... [more]

The shifting shadows of pagan times held sway over Ireland when the High King was a man known as Laoghaire, famed for his merciless fury and great strength, and he sat upon the seat of the High Kings in Tara. But unknown to him, Saint Patrick had landed in a little boat at Colpe in the Boyne estuary, travelling to a place called Ferta fer Feic, or ... [more]

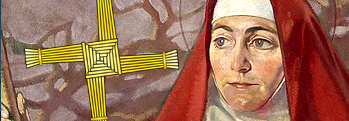

One of the three patron Saints of Ireland, along with Patrick and Colmcille, St Brigid of Kildare was a devout Catholic in the very first days of the faith in Ireland. Her feast day is the first of February, which previously had been the pagan festival of Imbolc, halfway between winter and spring. Brigid herself was the daughter of a baptised Ch ... [more]

Through many an ancient legend and tale rings the name of the fierce and powerful druid called Mogh Ruith, meaning “slave of the wheel”. Older legends make him out to be the king of the Fir Bolg, or a druid gifted with many lives by the fairies, or that the name was but a title passed down through generations. Some say he had one eye ... [more]

Ireland has had many high kings, some were wise and kind and others cruel and the holders of grudges, but there were few as great as High King Cormac Mac Art, grandson of Conn of the Hundred Battles and son of Art and Ectach, the daughter of a mighty blacksmith. In his youth he stayed at the hall of the king of the north, Fergus Dubhdedach, but ... [more]

Back in the days of old Ireland when legends walked the earth, before the light drove back the shadows of ancient aeons, the word of a bard was much feared, for the people had no writing, so all of their culture and histories were held in songs and poems by bardic masters. As you can imagine even the mightiest were wary of getting on the wrong s ... [more]

In ancient days there was an Irish King whose name was Labraid Lioseach, known also as Labraid the Sailor for a long voyage he took into fairy seas, and when he came back from that voyage he was never seen without a deep hood over his head, except by one man. That man saw him once a year to trim his hair, and after the King's hair was cut, t ... [more]

It was the custom in Ireland of old to lay geases upon champions, heroes and warriors. These were magical forbiddings, deeds they must not do or disaster would follow, and no disaster fell so hard upon a man who broke his geases as upon Conaire Mor! His mother was a woman of the Sidhe called Etain, who had been married to King Eochaid, but disco ... [more]

Tierna the Historian was one of the many chroniclers and monks who wrote the tales of ancient Irish legends, telling us of strange and notable events in the almost forgotten past, the deeds of heroes and kings, and in one case, the disappearance of the High king himself! For it was by Tierna's hand we know that High King Cormac went missing for ... [more]

In the time between the Tuatha Princes and St Patrick, there rose over the people of Ireland mighty High Kings, who held power by force of arms, wit and wisdom. One of the greatest among them was Cormac of the wide purple cloak, whose hair was as golden as the heavy torc around his neck, with teeth like a shower of pearls and skin as fair as snow. ... [more]

Long ago when the fierce Milesians invaded Ireland and defeated the De Danann after many wars and battles, despite their sorceries and all their courage, skill and sciences, the folk of Danann made for themselves eldritch amulets and charms by which they and all their possessions became invisible to mortals, and so they continued to lead their old ... [more]

The Tailteann games were a grand affair in Ireland once upon a time, every bit as celebrated and renowned as the Olympics are today. Having their roots thousands of years earlier, in the time of the Tuatha Dé Danann, lakes were made and gigantic fires were lit during Lughnasadh, the summer feast in July. Druids and poets would compose cea ... [more]

The Claddagh Ring is one of those well known emblems of Ireland that most people recognise, but how many know the stories behind it? Many's the young man has gifted one to his lady, giving his heart along with it, as did the ring's original maker. Back in the seventeenth century there was a young Irish lad by the name of Richard Joyce, w ... [more]

Ah Tara, Temair of old, seat of more than a hundred High Kings of Ireland for better than a thousand years, home to the royal lines of Cormac and Tuathal, where is your wisdom and beauty? Where are the mighty warriors and poets who once danced in your halls? Why now do cattle and livestock graze where the mighty Fionn faced the Tuatha sidhe with a ... [more]

On Easter Sunday morning, in anno domine 433 it was that Patrick came face to face with the beating heart of the old religion at Tara, and did battle with the Druids. Although some might dispute the miraculous nature of the events that took place on that day, few argue they didn't happen, so take from that what you will! Laeghaire the king a ... [more]

Brian Boru was one of the greatest High Kings of all Ireland, a Christian king whose small dynasty challenged and broke even the power of the O'Neills, who had ruled Ireland from time immemorial. He rose to prominence at a time when the cruel Norseman was pillaging the lands of both Ireland and England, slaughtering and slave-taking, barbarians ... [more]

King Suibhne was master of the northern land of Dalriada in Ulster, and a grim and fierce king he was too, yet fair to behold like palest snow, with deep blue eyes. A mighty master at arms, he was called to war often, but latterly to the bloody battle of Moy Rath. As he readied himself he heard in the distance a church bell ringing, and no man of G ... [more]